New MRI technique shows more details of brain activity during seizure.

Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientists may be close to unravelling a tragic mystery. Sudden death from epileptic seizure (SUDEP) is a poorly understood fatality that accounts for about 50% of deaths in people whose epilepsy is not controlled by medication. Dr. Stuart Cain and his colleagues in the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health have been hard at work developing a unique MRI technique that points to a possible cause of SUDEP. This new imaging innovation allows researchers to observe the brain inactivity (spreading depression) that can occur following a seizure.

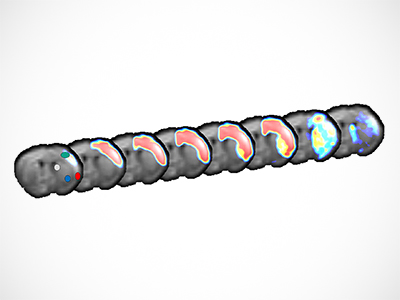

“Previously, we could only observe spreading depression by putting electrodes into the brain and measuring the electrical properties. We’ve been able to refine an MRI technique so that we can get a 3D moving image of how it invades different brain structures.”

On video you can see regions of the brain lighting up then going dark as spreading depression moves through. But it’s what happens after that wave of inactivity and swelling that may be crucial.

“During a seizure, cells undergo a period of rapid excitement, after which the nerve cells swell and go completely silent in certain brain regions. This inactive state can last for 5-10 minutes. In the case of fatal seizures, we are seeing that inactivity travels as deep as the brain stem—where breathing is controlled. When it reaches that region, breathing stops and death occurs. It’s our theory that this spread of inactivity to the brain stem is what leads to SUDEP.”

Other epilepsy research is looking into cardiac causes of SUDEP, but Dr. Cain says this new evidence is quite compelling. In the cases where trial subjects have seizures and recover, the wave of swelling is not reaching the brain stem.

“This is an exciting possibility for us to pursue. It has so much potential to also help us understand conditions like stroke and migraine which can behave in similar ways to seizure in terms of brain inactivity.”

Real world application?

For now, the new MRI technique is only a research tool. It can’t be used in human studies. But Dr. Cain and his colleagues are already experimenting with a promising drug to block the wave of neuronal inactivity following a seizure from reaching the human brain stem. “We are excited about a pain relieving drug that has already passed Phase 1 of clinical trials in humans. When we used this drug on the mice who are prone to sudden death from seizure, we doubled their lifespan.” The drug was developed in Vancouver and is now being used in trials elsewhere.

Dr. Cain works in the Terry Snutch laboratory at CBH—with access to state of the art MRI and electrophysiology equipment and a strong spirit of collaboration. “The centre creates a great atmosphere for research in a competitive and fast-moving field.”