Walk10Blocks helps get sedentary people moving.

The development process behind a new app to help sedentary people get moving shows how unique partnerships between researchers, consumers, and patient groups can lead to innovative health research. Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) scientists Dr. Linda Li and Dr. Teresa Liu-Ambrose credit the collaboration between themselves and consumer and patient groups, including Arthritis Consumer Experts, the Alzheimer Society of B.C., and CARP (the Canadian Association of Retired Persons), for the development of the Walk10Blocks app.

“We’re very proud of this collaboration. It’s a perfect example of how researchers getting together with patient and public groups can come up with innovative ideas and actually make things happen,” says Dr. Li.

“I’ve built apps before for other research projects and it usually takes a very long time. Walk10Blocks only took one year from conception to testing launch in the community. When consumer and patient groups are involved–they know what works and they’re really driven to get things done fast and done right.”

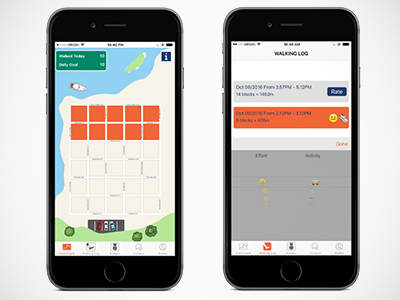

Walk10Blocks, which is currently available for free on iTunes, can be installed on an iPhone 5S or above. The app uses the phone’s core motion sensor to collect data about a person’s movement activity. The app converts this activity into a walking log, which tracks the distance travelled throughout the day and how many theoretical city blocks have been covered. The goal is to encourage sedentary people to walk at least 10 blocks per day. The app offers motivating, friendly alerts, has easy-to-read measurements, helps set reasonable walking goals, and awards badges for meeting goals.

By downloading the app, Walk10Blocks participants have also agreed to take part in an innovative research study that uses the app to collect data through surveys. Information gathered for the study includes patients’ fatigue, pain, mood, stress, and walk ratings to give researchers a better understanding of what individuals’ walking opportunities look like. The study also aims to help users recognize and understand their own physical activity levels and sedentary behaviour, create awareness about neighbourhood resources, and determine the overall feasibility of the app.

Development of the app started with one of Drs. Li and Liu-Ambrose’s research groups consulting with patient groups and receiving a grant from the Improving Cognitive and Joint Health Network (ICON), a Canadian Institutes of Health Research knowledge translation catalyst network.

“What we heard loud and clear through our consultations was a desire for more efficient, effective use of what we know about physical activity and its health benefits in terms of managing diseases, especially for people whose health may worsen without it.”

Early on, the groups met with Dr. Liu-Ambrose, researcher at the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health and the Centre for Hip Health and Mobility, who shared with them current evidence with relation to exercise and cognitive function. According to Dr. Li, the group was most interested in findings from a nine-year observational study in the U.S. that showed that walking approximately 10 city-sized blocks results in better cognition and better brains.

“That specific information had our consumer groups almost jumping for joy because to them it was finally something concrete that could be used and brought back to stakeholder groups as the minimum amount of physical activity you needed to do for positive effect,” according to Dr. Li.

“The evidence is accumulating to suggest that exercise is beneficial–but where there is a void is how to put it into action. The app is a bit of that component,” she adds. “When everyone has a common goal and shared interests, I think that’s when we make good progress.”

“And so in many ways, recommending regular activities, such as moderately paced walking, seems to be a pretty reasonable approach for promoting physical and cognitive health over the lifespan.”