How the medical community is responding to climate change.

This summer’s heat waves had people scrambling for ways to stay cool. In the Lower Mainland pool hours were extended, cooling centres were set up to prevent heat-related illness and power usage hit an all-time high. Ongoing wildfires and poor air quality in the interior were another reminder that global warming’s effect on our health has never been more evident.

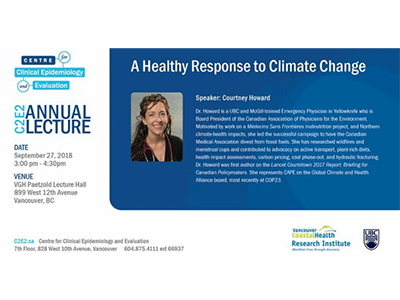

Globally, the World Health Organization has declared climate change to be the greatest threat to human health. The message of the upcoming annual public lecture from the Centre for Clinical Epidemiology and Evaluation (C2E2) is that health professionals have a pivotal role to play in responding to this threat. This year’s keynote speaker, Dr. Courtney Howard, is a research scientist and emergency physician from Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. Howard says climate change has direct impacts on public health, and Canadian health providers have a responsibility to both prepare a response and work on mitigation.

“We own this problem whether we want to or not. We are already responding on a clinical level to the impacts of climate change—whether it’s more lung disease diagnosis from increasingly severe forest fires, or death and illness from heat waves or rising cases of Lyme disease as more ticks survive our warmer winters.”

Howard says physicians and researchers have always had a duty to prevent and respond to threats to human health. “In the case of illness such as heart disease, lung cancer or diabetes we look upstream at things like sugar intake and smoking habits, and we engage in prevention efforts. Climate change is no different and we have an ethical duty to prepare for it.”

Howard is also the 2018 International Policy Coordinator for the Lancet Countdown, a 15-year project to determine the best responses to climate change and the best initiatives to combat it. She says health professionals, such as doctors and nurses, have a vital role in educating the public. Polls show people are more motivated by health concerns than any other factors when it comes to climate change, and people trust doctors and nurses much more than they do politicians. “We own the most effective message and we are the most trusted messengers.”

Health care providers and researchers have the responsibility and the privilege to make the biggest impact on the defining issue of our time.

Howard says health providers and researchers are not always aware of how much power they have. In Ontario, she says, health providers were key players in bringing about the shut down of coal fired power plants, a move that improved air quality, lowered greenhouse gas emissions and reduced hospital admissions.

As a physician practicing in Northern Canada, Howard says she sees the impact of climate change every day. “The average temperature in Inuvik is already three degrees warmer than it was in the fifties. We are seeing loss of permafrost and its impact on traditional hunting and culture. We are seeing huge economic costs. No one up here is a climate change denier.”

Health impacts range from increased lung disease from bad air quality to mental health impacts from the loss of homes and lost income due to prolonged evacuations.

Better climate change response, better public health

The dire predictions for our warming planet can sometimes be overwhelming. But Howard says by crafting our response and actions around protecting human health, we can see immediate benefits and feel more empowered.

“When we reduce air pollution, use cleaner transportation and switch to a more plant-based diet we feel better and we save lives as we decrease greenhouse gas emissions. We do have an impact. We need to get that message out.”

Howard will be calling on health researchers to consider the effects of climate change as part of their work. “Climate change needs to be on the radar of every researcher. It impacts everything going forward.” She’s also working with medical students to push for climate change to be included in medical school curriculum in Canada.