Cognitive impairment a new focus for spinal cord injury research.

When people think of spinal cord injury (SCI) they tend to focus on paralysis and body movement. But post-injury, the biggest health risk is actually cardiovascular disease— it’s the number one cause of disability and death in people with SCI. Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientists at ICORD (The International Collaboration on Repair Discoveries) are focusing on cardiovascular problems in SCI patients, in particular their inability to regulate blood pressure (BP). They’re especially interested in how BP dysregulation is linked to cognitive impairment. It’s an important focus: in a recent review study in Neurology magazine, Dr. Andrei Krassioukov and colleague Dr. Rahul Sachdeva found up to 60 per cent of people with SCI demonstrate some degree of cognitive impairment.

The average age for SCI is 29 years old. With improvement in care, patients are now living much longer so quality-of-life research has become more valuable. Sachdeva says cognitive ability should be a big part of that focus. “We want to highlight cognitive health because it is really what defines who we are personality wise. If you’re not cognitively well, it impacts your own wellbeing and affects everyone around you.”

“Most spinal cord injury happens early in life. If you are injured at a young age, you need to be able to resume normal life, to return to work and socialize.”

Through their work, Krassioukov and Sachdeva are unravelling the connections between high rates of BP dysregulation and high rates of cognitive impairment. Krassioukov says it is an area of research that requires urgent attention.

“Most people with SCI have problems with BP regulation. In the same person, it can be too low and then with just a slight stimulus—like a full bladder or a shoe lace that’s too tight—it can triple to dangerous levels.” In these situations, damaged nerves are sending the wrong signals to the brain. Blood vessels go into overdrive and narrow or widen excessively, raising the risk of either passing out, or having a stroke or heart attack. “This is a typical occurrence for many of my patients,” says Krassioukov.

“It’s like a yo-yo effect. One moment their BP is too low, the next, it overshoots and becomes dangerously high. Unfortunately there is no drug that can keep them in the safe zone.”

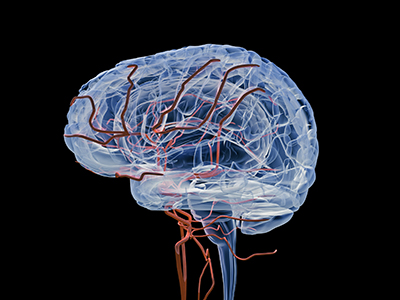

The blood pressure to brain connection

All of this fluctuation takes a huge toll on the brain, which needs a large supply of oxygenated blood to keep neurons functioning normally. “Blood vessels need to maintain a stable pressure inside the brain,” says Sachdeva. "The brain has to adjust to the systemic pressure of the body. For people having these yo-yo episodes multiple times a day, their brains have to keep readjusting. But they have a limit. And after a while they give up.”

Krassioukov also notes that the changes in brain vessels in SCI patients mimic those found in able-bodied individuals who have hypertension and develop vascular dementia.

Both researchers are looking for ways to restore normal cardiovascular control and prevent cognitive impairment for people with SCI. These innovative approaches include transplanting peripheral nerves to build a "bridge" from the brain, pharmacologically repairing part of the spinal cord, and implanting epidural devices to externally stimulate the body in an effort to better regulate BP.

Krassioukov says getting blood pressure under control for SCI patients will have a ripple effect of benefits, not only for patients as it would decrease rates of depression and ischemia, but it would also reduce health care costs significantly—SCI patients often have to be hospitalized for hypertensive crises.

More importantly, Sachdeva points out, BP control is at the top of the wish list for ICORD’s patients. “Surveys of SCI patients show that walking again is not their highest priority. Their autonomic dysfunction–loss of bladder control, inability to control blood pressure—is considered a higher priority than walking again. It’s quality of life.”