OVCARE continues building success through partnerships, now as part of Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

Around Christmastime in the year 2000, three clinician researchers got together in Vancouver General Hospital (VGH)’s cafeteria to discuss a common frustration: too many women were dying from ovarian cancer. Despite global research efforts, back then the five-year survival rate for women with the disease was less than 50 per cent. Fuelled by a desire to improve those outcomes, the three doctors sketched an outline—on the back of a napkin—for a concentrated, multi-disciplinary ovarian cancer research effort.

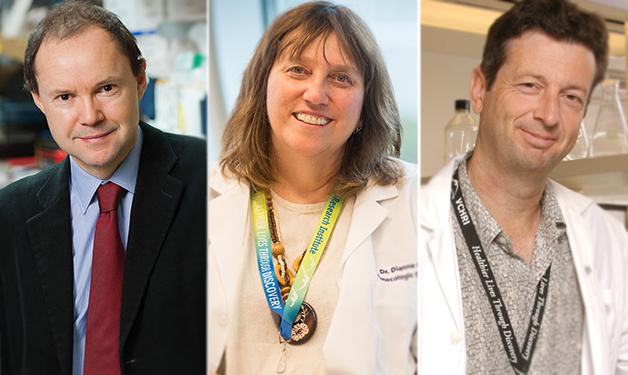

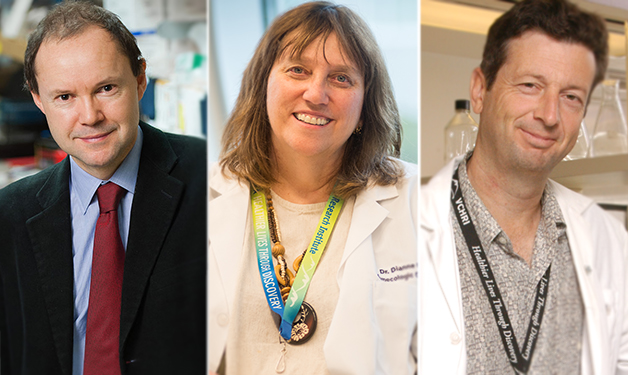

Sixteen years later, the doctors—gynaecologic oncologist Dr. Dianne Miller, geneticist Dr. David Huntsman, and pathologist Dr. Blake Gilks—continue to work together successfully as co-founders and co-directors of the Ovarian Cancer Research Program (OVCARE). The organization now comprises more than 50 team members located at VGH, the BC Cancer Agency (BCCA), and the University of British Columbia (UBC), and recently became a research centre within the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI).

“We were very grateful and fortunate to get the support of the BC Cancer Foundation and VGH & UBC Hospital Foundation and later from UBC Faculty of Medicine Office of Development who all thought ovarian cancer was important enough that they needed to work together as a team. And we’re very pleased now to be part of VCHRI,” says Dr. Huntsman, professor of gynaecologic oncology and professor in the Department of Pathology and Department of Lab Medicine and Obstetrics and Gynaecology at UBC. “With this support and the great generosity of the women of B.C. who are our research partners, we have grown from an idea to being one of the top three ovarian cancer research centres in the world in terms of productivity and our ability to use research to decrease death and suffering from the disease.”

“OVCARE marked the first time the foundations worked together to support a major research program. And our clinicians and researchers worked together to build research resources such as a tumour bank and outcomes unit to support ovarian cancer research.”

Dr. Huntsman describes OVCARE’s starting point as unique. The researchers took a step back to ask the simple question of why, despite the many brilliant people around the world studying or thinking about ovarian cancer, so little progress was being made. In other words, why had research failed to improve outcomes in clinics? Their breakthrough response was that researchers were studying ovarian cancer as though it was one disease, when it was a mixture of diseases.

“Up until then we were looking for something impossible—a solution that could work across many different problems,” explains Dr. Huntsman a VGH pathologist, who is also a distinguished scientist in the Department of Molecular Oncology at the BCCA Research Centre and Canada Research Chair in Molecular and Genomic Pathology. “So we put considerable effort into studying the structure of the problem as well as how many different types of ovarian cancers there were. We wanted to create a blueprint of how ovarian cancer should be researched and treated but also develop the tools to better classify different sub-types in the clinic.”

OVCARE’s sub-type specific approach to treatment is now the gold standard internationally and the underlying driving hypothesis behind everything the organization does.

“The sub-type approach means that the different types of ovarian cancers have different biologies and are associated with different clinical challenges. We’ll only make progress if we look for new ways of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment, which reflect those differences. This was a very empowering concept.”

The concept led OVCARE to discover key mutations in several types of ovarian cancers, which allowed for new diagnostic approaches and changed the way in which those cancers were managed. It also led to a prevention program–the first population-based prevention program for ovarian cancer–in which OVCARE acted on existing research that ovarian cancers likely start in the fallopian tubes and not the ovaries. OVCARE suggested that fallopian tubes be removed during routine procedures such as hysterectomy and in lieu of tubal ligation in an effort to prevent ovarian cancer, subsequently changing surgical practice in B.C. This made-in-B.C. solution to preventing ovarian cancer is now the international standard but the women of B.C. have benefitted first.

“Fallopian tubes weren’t removed in the past because there was no reason to remove them,” says Dr. Dianne Miller, head of B.C.’s gynaecologic cancer clinical team. “Now there’s a reason. This has been taken up internationally and has become a standard of care. A lot of our research now is directed toward determining what portion of ovarian cancers we will prevent.”

Because of OVCARE’s successes, Dr. Huntsman says they are now expanding and broadening research to focus on other gynaecologic cancers, such as endometrial cancer.

“We’re taking the model of success of OVCARE and expanding outside of ovarian cancers,” says Dr. Huntsman. “We believe that if our team is appropriately resourced, we could decrease death and suffering from these cancers by 50 per cent in the next 15 years.”

“That’s the goal that’s driving us now. It’ll take a lot of work, but we know as a team we can do much more together than as individuals.”