“I say yes to participating because that’s the only way we’re going to learn more about injuries like concussions and brain trauma. The more data the better.”

– Aaron Brown, Vancouver

Thirty-year-old Vancouver resident Aaron Brown has experienced concussions in the past, but a concussion two years ago—from a cycling accident that launched him into a ditch—felt different. It has been a slower than usual road to recovery and Brown still doesn’t feel 100 per cent.

“I’ve had multiple concussions before that were much worse when they happened. I didn’t think this one was bad at the time, but the symptoms kept wearing on,” says Brown, an accountant. “As time passed, I had this fuzzy or disoriented feeling about me, especially during tasks that involved a lot of mental effort. When I was exercising or doing physical activity, I felt fine. But when I was stressed at work, everything seemed to cloud up a bit.”

Soon after the accident, Brown saw a physician who gave him a concussion diagnosis. Because he had been through concussion protocols before, he knew to take things easy, but he found it discouraging not knowing definitively how severe the injury was or what to do to recover.

“It’s as though you’ll get 20 different opinions if you talk to 20 different people about concussions,” says Brown.

“I took it easy for about a week but never really got much better.”

Brown heard through a friend about a concussion clinical study and decided to take part. The study is currently recruiting more participants.

The study is assessing whether a novel system for tracking eye movements can provide an objective and more sensitive way to better analyze and diagnose concussions quickly.

Jacob Stubbs, a research assistant at the University of British Columbia (UBC)-Vancouver General Hospital Human Vision and Eye Movement (HVEM) Lab, Dr. Jason Barton, Director of the HVEM Lab, Canada Research Chair and Marianne Koerner professor of Neurology, Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, and Dr. William Panenka, an assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at UBC, are conducting the research.

Stubbs’s personal experience with a severe concussion in 2014 sparked his interest in looking at eye movement as a possible indicator for concussion or mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI).

“After my concussion, I found that when I was looking at my phone trying to scroll up text messages, my eyes would jerk all the way up instead of following it smoothly,” says Stubbs, who is a student in the School of Kinesiology at UBC. “After recovery and while working at the HVEM lab in the field of neuro-opthalmology, I thought back to my injury and wondered if there was a project I could run to help contribute to the field.”

Eyes on target

Stubbs describes the eye tracking diagnostic tests as “strikingly simple.”

The study focuses on tracking the eyes’ smooth pursuit movement, which is a type of eye movement modulated by attention and used to smoothly pursue a target. Study participants place their head in a head mount, look at a screen, and do one minute of a reaction time task, then two minutes of eye movement tasks. The first eye movement task assesses baseline smooth pursuit of a target moving in a circle, and the second task examines smooth pursuit while performing the reaction time task. Results from the baseline reaction time, baseline circular pursuit, and combined tasks are then analyzed, along with a neuropsychiatric questionnaire battery.

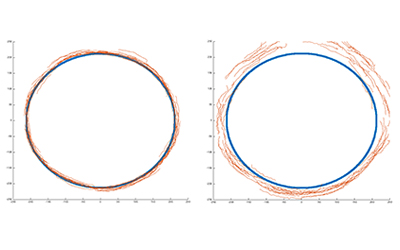

Test results for healthy controls show that their eyes are able to closely track a visual target, which is a simple dot moving around a circular trajectory. For patients with concussion or mild traumatic brain injury, however, their eyes tend to deviate more inwards and outwards, ahead or behind the target, resulting in a more variable spread surrounding the target.

Dr. Panenka, who is a member of the British Columbia Provincial Neuropsychiatry Program and medical lead at the Neuropsychiatry Concussion Clinic and Fraser Health Acquired Brain Injury Concussion Clinic, says eye movements are exciting research avenue because many of these movements are not under conscious control, which circumvents many issues with other concussion tests where performance can be affected by many other factors distinct from the brain injury.

“Discovery of an objective, reliable biomarker of concussion is critical to the patient's subsequent medical management and would also allow us to evaluate the utility of the many treatments currently available,” explains Dr. Panenka. “It may also help tell us when a person is fully recovered, which is critical to decisions related to return to work, school, and play.”

“There are also many different brain pathways that all converge to make eyes move–it’s not just one region in the brain.” Dr. Panenka goes on to say that the circuitry that controls our eyes traverses essentially the entire brain, so eye movements have the potential to capture an injury over wide areas. This is very important in brain trauma as the nature of the injury is spatially heterogeneous–one concussion generally does not result in the same areas of damage as the next.

Due to these advantageous qualities, the literature around eye movements is “exploding,” says Dr. Panenka. “It is looking very much like one of the most promising physical signs of concussions.”

“What we’re trying to find through our work are some of the holy grails of concussion research: a way to accurately diagnosis a person’s concussion when they’re first injured and a way to objectively follow their recovery,” Dr. Panenka adds.

THIS IS ONE PATIENT’S STORY OF PARTICIPATING IN A CLINICAL TRIAL. YOUR EXPERIENCE MAY DIFFER. LEARN MORE ABOUT CLINICAL TRIALS BEFORE PARTICIPATING.