How children’s bodies respond to different meningococcal disease vaccines could help decision-makers pick the most effective one.

Vaccination is the best line of defense against meningitis, and determining whether three vaccines used to protect against a leading type of the disease are equally effective is the focus of research being conducted by Dr. Manish Sadarangani, a Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher. His clinical trial aims to inject additional clarity into the administration of meningococcal C vaccines across Canada.

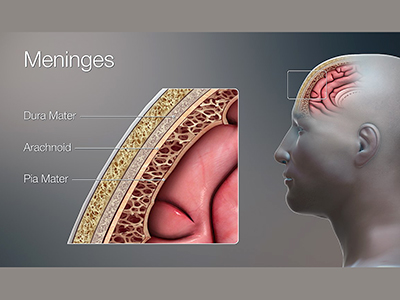

Meningitis is caused by a bacterial or viral infection that invades the tissues covering the brain and spinal cord, called the meninges. An acute onset of the disease is often characterized by a fever, intense headache, stiff neck and nausea, among other symptoms.

“Even with all the treatments and modern medicine we have today, up to 10 per cent of infected patients still die from meningococcal disease.”

The viral version usually does not cause serious illness; however, bacterial meningitis, while less common, can lead to death if left untreated. Both versions can have lasting health effects, such as brain, hearing or vision damage, as well as behavioural and emotional changes.

Children and babies are most vulnerable to acute meningitis—caused when the disease invades the bloodstream—due to their developing immune systems.

The three types of bacteria responsible for the vast majority of bacterial meningitis cases in Canada for the past several decades have been Haemophilus influenzae, which is now greatly controlled thanks to immunization; Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), which remains a leading cause of meningitis; and Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcus), which is a primary cause of meningitis among children and youth. The main types of meningococcal infection in Canada are: B, C, W and Y.

Protecting young patients with the best vaccine

Immunization against meningitis began in Canada in 20021. Since then, infection rates have steadily declined from around 150-200 cases per year between 1997 and 2012, to closer to 100 cases per year after 20132. However, acute cases of the disease continue to be a significant concern due to their potential damaging effects and high rate of mortality.

Babies receive vaccination against meningococcal C as part of their routine immunization schedule. A MenACWY booster shot is then administered around Grade 9 or age 12.

“The ideal way to treat meningitis is to prevent it through vaccination.”

Sadarangani’s research examines children’s immune system response to the meningococcal C component of three different types of MenACWY booster shots.

Together with his research team, he is evaluating how the dosing of the meningococcal C vaccine children received as babies impacts how their bodies react to the C component of the MenACWY booster shot they receive later in life.

Researchers are particularly interested in how well patients’ immune systems are able to produce antibodies that can fight off and eliminate the disease.

The research team will check the antibody levels of youth before they receive the vaccine and then one month and one year after inoculation.

The data points generated by their results, scheduled to be released in summer 2021, will provide new insights into how the MenACWY vaccines stack up against one another.

“We are hoping to find that all the vaccines tested are equally effective in terms of how well they induce an antibody response.”

Sadarangani anticipates that this research will guide decision-makers on which vaccine best fits the bill.

1 Government of Canada - Invasive Meningococcal Disease

2 Government of Canada - Vaccine Preventable Disease: Surveillance Report to December 31, 2017