Magnifying mistakes leads to more meaningful motor learning.

Experts commonly advise that the best exercise is exercise you enjoy doing—that way you’ll keep doing it. The same holds true for rehabilitation exercise, especially when it comes to younger patients. Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientists recently tested gaming devices equipped with immersive virtual reality (VR) technology to see if they motivated teenage patients with cerebral palsy to improve their motor learning. Initial results show VR was well received by patients and was successful in improving outcomes, making it worth pursuing further. Biomedical engineer Leia Shum designed the study under the guidance of Dr. Machiel Van der Loos.

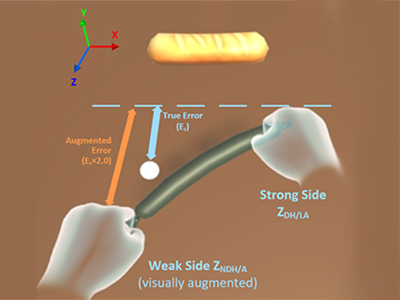

“EA is a way of putting a visual weight on things,” explains Shum. “In real-life these patients don’t have an accurate perception of how they move. With virtual reality we can manipulate what they see. We make it more obvious which body part needs to work harder so their brain will correct the movement.”

"Through game challenges, we are able to change the way patients see themselves move. It’s quite powerful and something we can’t do as well in real-life physiotherapy sessions.”

Shum incorporated two-handed tasks into the games—such as carrying a tray or laying out food items—and then visually increased the distance the weaker limb had to reach, triggering the brain to move the weaker limb as much as the stronger limb.

“Even if a person thinks they are moving both arms equally," says Shum. "We can manipulate the image to show them they are not, in an effort to trigger their brain to change that movement.”

While the study was small, Van der Loos says it accomplished a lot. In just one session of so-called exergames, participants with cerebral palsy improved their ability to reach with their weaker limb. “We established that this intervention has great potential. People with hemiparesis (paralysis affecting one side of the body, or partial paralysis) can essentially retrain their brain using virtual reality.”

Home court advantage

Van der Loos says because the VR software and hardware in the study are commercially available, it could be used in the home setting. This would improve both patient outcomes and access. “Typically, people need way more exercise therapy and practice than their health care plan will allow for. Having a fun, low-cost robotics tool you can use at home will enable people to practice and meet goals that are motivated more by the activity itself than by it being something they have to do.”

Shum says another huge advantage is that with the VR games, therapists can quantitatively control stimuli and set more concrete goals, even by phone or Skype check-ins. “In the clinic, physiotherapists can only give verbal cues; using VR we can give patients an exact number as to how far away they are and how much they need to move. This can be incredibly motivating, as they can see and measure their progress in real time.”

However, Shum stresses that at-home use of VR exergames is meant to complement, not replace physiotherapy and clinical visits. As such, there’s no reason the VR technology can’t be used with older people, including seniors.

“Once someone is trained in how to set it up, it is fairly straightforward to use. Seniors often enjoy the gaming aspect too.” Shum notes some senior centres already use VR games to motivate and encourage residents to be more physically active.

Both Shum and Van der Loos note that VR therapy has potential to be used in a wider range of motor disorder rehabilitation, including stroke recovery. They are hoping longer-term studies, with more participants, can be done in the future.