Findings contribute to baseline knowledge of minute-to-minute healthy brain activity.

Examining the brain when it is healthy is essential in order to understand how and why things go wrong when they do. Interested in the brain in its healthy state, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute investigators from the Djavad Mowafaghian Centre for Brain Health’s (DMCBH) Dr. Brian MacVicar Lab asked novel research questions about communication between the brain’s neurons and microglia, its immune cells. The team’s subsequent discoveries, which were recently published in The Journal of Neuroscience, demonstrate that neurons can communicate with microglia using a signalling molecule called ATP (adenosine triphosphate, a molecule normally responsible for energy transfer within cells).

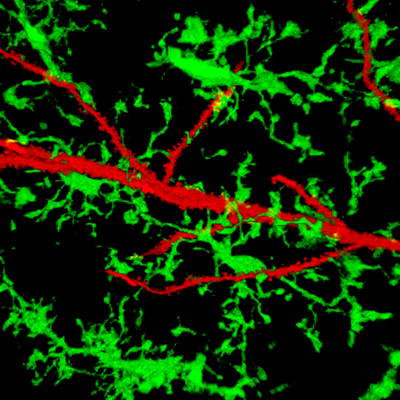

“We were curious about the function of these microglia cells, which are found throughout the entire brain and exhibit motile processes that survey their surroundings,” says lead author and PhD student Lasse Dissing-Olesen. “We wondered if they would be able to sense neuronal activity.”

To determine this, Dissing-Olesen and his colleagues repeatedly stimulated neuronal activity and found that the microglia altered their morphology in response to this neuronal stimulation.

“Thanks to cutting-edge imaging technology and combining research techniques, we were able to observe in real-time what was happening to the microglia cells when we repeatedly stimulated the neurons,” explains Dissing-Olesen.

Creating a baseline for a healthy brain

Taking their research further with the unique idea of having one neuron communicate with surrounding microglia, the team combined different lab techniques and discovered that neurons communicate with our immune cells via ATP. The group’s discovery is a significant step toward better understanding the communication between neurons and microglia when the brain is in a ‘normal’, healthy state.

“Neuroscience needs a better understanding of the normal functions in the healthy brain – a baseline – so that we can later understand things when they go wrong,” says Dissing-Olesen.

“It is amazing how the brain works when you think about it. Instead of just looking at the dark side when things aren’t healthy, we need to understand the complex dynamics that keep the brain going.”