Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation offers effective, accessible, minimal side-effects option to medication.

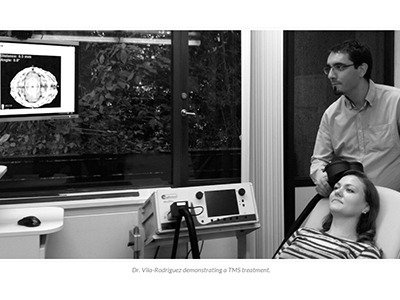

As though suffering from depression was not challenging and debilitating enough, some sufferers find no relief from treatment or experience side effects to medications that make taking them impossible. An estimated 22 per cent of Canadians with major depressive disorder have such treatment-resistant depression (TRD). While the situation may seem hopeless, one therapy called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) has shown significant efficacy as a non-invasive procedure with minimal side effects, offering a viable treatment option. Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientist Dr. Fidel Vila-Rodriguez is hoping to find a way to make rTMS more accessible and available to people with TRD.

“There’s a huge need to find alternative treatments that don’t have such harsh side effects or that provide relief for people with TRD,” says Dr. Vila-Rodriguez, clinical associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and director of the Non-Invasive Neurostimulation Laboratory & Schizophrenia Program at UBC Hospital.

“That’s where rTMS has found its role because according to the latest meta-analysis it reaches an efficacy rate that’s very high for treating TRD: 50 to 55 per cent response rate and 30 to 35 per cent remission rate.”

rTMS involves using a pulsating magnetic field to stimulate targeted areas of the brain. How exactly the therapy works is not completely understood, however, repeated TMS treatments seem to improve how these brain areas and circuits operate and help with depressive symptoms in some people. TRD patients prescribed rTMS typically have to receive the treatment for 40 minutes every day for six weeks.

Dr. Vila-Rodriguez is leading at UBC a multicentre study to determine whether a new stimulation protocol that reduces the time needed for each treatment to only three minutes (rather than 40) is as effective as conventional treatment standards. He is also examining the efficacy of a new method of stimulation called theta burst.

“These two possible changes will impact the availability and capacity of clinics to offer the treatment to more people,” he says.

“If our hypothesis of the study is supported by data, there will be two groups for whom this research will benefit: for patients receiving treatment, the shortened treatment time will be a lot more convenient and will make the visit to the clinic almost as short as a coffee break,” says Dr. Vila-Rodriguez. “And it’s a game-changer for clinical practice because suddenly an appointment that would normally take an hour could be reduced to 15 minutes, which is a generous estimate."

"By increasing the capacity of the clinic, the cost of having a device and personnel is reduced and the system becomes more efficient.”

Switching to the theta burst method of stimulation would deliver more stimuli within each burst.

“Theta burst is a good tool is because the rhythm of five (theta) bursts per second actually mimics a rhythm that we all have in our brains,” explains Dr. Vila-Rodriguez. “It seems that certain parts of our brain communicate at that rhythm and that’s why earlier studies were completed trying this type of stimulation.”

“The fact that rTMS offers minor side effects such as mild discomfort or headaches, or the rare possibility of a seizure during stimulation, make it a better suited treatment for many people suffering from TRD,” he adds. “What I’m envisioning is that really rTMS can be a treatment that can be incorporated into someone’s schedule easily without much interference in their daily life.”

The study, which is a collaborative effort between Dr. Vila-Rodriguez’s lab and the Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (Toronto) and Toronto Western Hospital, aims to recruit 300 participants between the three sites.

Visit Ninet for more information about how to participate.