News Release | About 7200 new cases of melanoma are reported every year in Canada, this new technology could be used as a preliminary screening tool for this skin cancer.

Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer, is diagnosed in more than 130,000 people globally every year. Now, work is being done on a tool to help in its early detection: a simple, compact laser probe that can distinguish between harmless moles and cancerous ones–in a matter of seconds.

“With skin cancer, there’s a saying that if you can spot it you can stop it–and that’s exactly what this probe is designed to do,” said researcher Daniel Louie, a PhD student who constructed the device as part of his studies in biomedical engineering at the University of British Columbia. “We set out to develop this technology using inexpensive materials, so the final device would be easy to manufacture and widely used as a preliminary screening tool for skin cancer.”

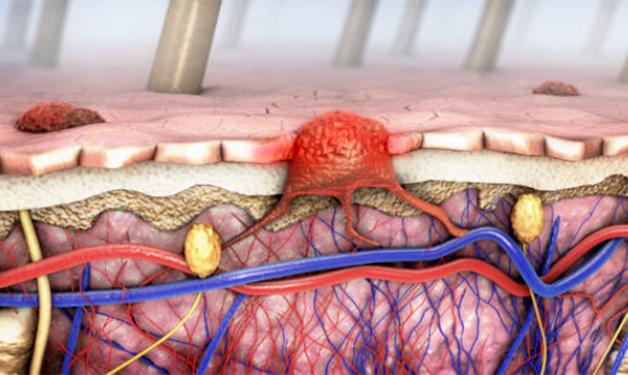

The probe works on the principle that light waves change as they pass through objects. The researchers aimed a laser into skin tissue from volunteer patients and studied the changes that occurred to this light beam.

“Because cancer cells are denser, larger and more irregularly shaped than normal cells, they cause distinctive scattering in the light waves as they pass through,” said Louie. “We were able to invent a novel way to interpret these patterns instantaneously.”

Imaging devices to assist cancer detection are not new, but this optical probe can extract measurements without needing expensive lenses or cameras, and it can provide a more easily interpreted numerical result like those of a thermometer. Although the probe’s components cost only a few hundred dollars total, it is not envisioned to be a consumer product.

“A cancer screening tool should be administered by a trained health care professional who would know where the patient needs to go afterwards,” said Tim Lee, an associate professor of skin science and dermatology at UBC and a senior scientist at both BC Cancer and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute, who supervised the work. He believes the device would be a good future addition to standard cancer screening methods, but not a replacement.

Noting that about 7,200 new cases of melanoma are reported every year in Canada, Lee believes the probe can promote early detection of this cancer.

“We have so few dermatologists relative to the growing number of skin cancers that are occurring,” said Lee. “If we can develop a device that can be integrated easily into other parts of the health care system, we can simplify the screening process and potentially save hundreds if not thousands of lives.”

The study, described in the Journal of Biomedical Optics, involved 69 lesions from 47 volunteer patients at the Vancouver General Hospital Skin Care Centre and is a joint project among UBC, BC Cancer and VCHRI. For their next steps, the researchers hope to eventually achieve Health Canada certification and approval before being able to offer this testing through health professionals. This will require further refinement of their technology and additional clinical testing in more patients.