Innovative MRI technology offers a rare glimpse into head injuries in two studies.

If Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientist Dr. Alexander Rauscher has learned anything from studying concussions that happen during sports like ice hockey, it’s that helmets really can only protect so much – and it’s not enough.

Dr. Rauscher, a physicist and assistant professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Radiology within the Faculty of Medicine at the University of British Columbia (UBC), and his research team embarked on two studies looking at concussions that specifically sought to collect data on the healthy brains of people who were likely to sustain a concussion, in this case hockey players. Their cohort comprised 45 21-year olds belonging to two varsity ice hockey teams.

“We scanned their brains before their hockey season started, then we waited for the concussions to happen and scanned them three days, two weeks, and two months post-injury,” explains Dr. Rauscher, who is also with the UBC MRI Research Centre. “To our knowledge, nobody has ever done this before – looked specifically at the same brains pre- and post-concussion – probably because it’s difficult to put together a group of individuals who are highly likely to experience this injury and it requires a lot of organization and financial support.”

“Ours are the first studies in humans to use imaging data before any injuries are attained during play, so we can compare the brain before and after. All other previous research has looked at two separate groups: concussed people and a non-concussed control group and the differences between their brains.”

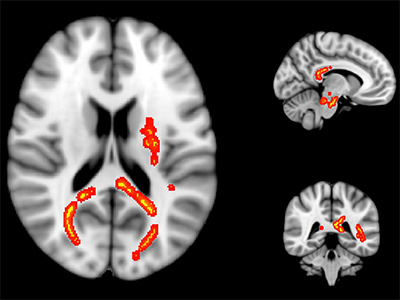

The first of two papers published by Dr. Rauscher and his research team earlier this year appeared in PLOS ONE and found that concussions reduced the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) signal associated with the brain's myelin content. In other words, their findings suggest a reduction in myelin itself, the protective coating that covers nerves. Damage to myelin causes signals to the brain to slow down and may also lead to the nerves themselves becoming damaged.

“We found that the myelin does recover post-concussion likely around or after three weeks and before two months,” explains Dr. Rauscher. “However, at two weeks, even though the concussed players were symptom-free, we still saw damage to the myelin. That’s the problem – if they get another hit, another concussion, that damage is still there and that may lead to something more permanent, like post-concussive syndrome where they may not be functional for months or a year.”

The researchers’ ability to detect the actual damage done to myelin was made possible by using a novel myelin-specific MRI scan developed by MRI scientists at UBC. The technology is not widely available yet, making Dr. Rauscher and his research team’s myelin study the first of its kind in people with mild traumatic brain injury.

Dr. Rauscher and his colleagues herald the fast myelin scan as a game-changer because a whole brain scan allows researchers to do new kinds of neuroscience research that had been impossible with a scan that only gives a thin slice of the brain.

“By using this pioneering scan, we were able to confirm that the MRI signal associated with myelin is reduced,” explains Dr. Rauscher. “For our research, we had to make the scan much faster first. We needed to map the entire brain and then investigate because with a concussion you don’t know where damage happens.”

Brain shrinkage after a season of playing hockey

The team’s second study, published in Frontiers in Neurology, found that all of their participants’ had a small loss in brain volume over the course of the hockey season, including players who didn’t suffer from a traumatic brain injury or concussion.

“We think it’s because the concussed had concussions and those without concussions had more impacts because they played more games,” says Dr. Rauscher. “Our hypothesis is that all of the impacts on the brain during the hockey season contributed to the reduction in brain volume. However, this requires further investigation.”

The big question remaining now is what happens to the brain in terms of recovery between hockey seasons.

“It would be very interesting to look into whether or not the brains continue to shrink or recover over the seasons, because if they continue to shrink that wouldn’t be that great – but we don’t know that.”

Dr. Rauscher believes that while helmets are helpful, they can’t sufficiently protect the brain from the myelin damage and brain volume loss that happens during games. In his opinion, the sport itself may need to change.

“Kids at 15, 16, 17 years old, or in first-year university, if they have a concussion and another concussion, that could be life-changing because they may not graduate from high school or do poorly in their first critical year of university; it could make the difference between having a good career in university or dropping out,” he says. “During that time when we should be highly functional, we shouldn’t be non-functional for weeks or months.”