Unique treatment-resistant models show proteins from the blood-borne disease successfully deliver molecular bombs to bladder cancer cell targets.

In the fight against bladder cancer, a new and unexpected hero is emerging: malaria. Recently published findings from a study led by Vancouver Prostate Centre (VPC) researcher Dr. Mads Daugaard show the efficacy of using a specific malaria protein to transport a toxin to bladder cancer cells in mice, reducing or deleting bladder cancer tumours entirely.

“This is very encouraging news for bladder cancer patients who currently have very limited treatment options. Cisplatin-based chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, but responses are rarely durable, and the only established second-line therapy is immunotherapy, to which only 20 per cent of patients respond,” explains Dr. Daugaard, head of the Molecular Pathology & Cell Imaging Laboratory and senior research scientist at the VPC and the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute.

“Our findings potentially offer a much-needed second line of treatment for patients with the more aggressive, treatment-resistant form of the bladder cancer.”

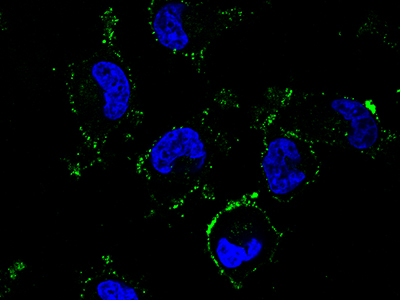

The study builds on Dr. Daugaard and his colleagues’ groundbreaking work, published in Cancer Cell in 2015, that first explored the concept of using refined malaria parasite proteins to target tumours. They found that the malaria parasite produces a protein that binds to a particular type of sugar modification found on the surface of most cancer cells. The researchers theorized how they could use the malaria protein to detect and potentially target that sugar structure.

For their most recent research, detailed in the top tier journal European Urology, the team’s challenge was to develop a proof of concept that they could specifically target cisplatin-resistant bladder cancer using the malaria protein armed with a cell toxin.

“We decided to focus on bladder cancer because we knew that our sugar molecule was present in high levels in bladder cancer,” says Dr. Daugaard.

“We discovered through our research that bladder cancer patients with high levels of this sugar molecule after cisplatin-based chemotherapy did much worse than patients with low levels” he explains. “We also discovered that if a patient relapses and the bladder cancer tumour comes back, that tumour would often have even higher amounts of the sugar molecule.”

The study showed that when treated with the malaria protein alone or the cell toxin alone, the cisplaten-resistant tumours did not respond at all and instead grew aggressively. However, when treated with the toxin-armed malaria protein, the researchers were able to completely shut down cisplatin-resistant bladder cancer. This is because the malaria protein can seek out the tumour and facilitate specific delivery of the cell toxin inside the tumour cells.

“Our results were quite remarkable and led to a very dramatic increase in survival among our murine patients.”

These findings couldn’t come soon enough as bladder cancer has an immense clinical need right now, says Dr. Peter Black, co-investigator, urologist, and senior research scientist at the VPC.

“It’s the fifth most common cancer in western countries and also the most expensive cancer to treat on a per patient basis for our health care system.”

Dr. Daugaard and the research team are aiming to conduct clinical trials at the VPC and he’s hopeful that they can start as early as two years from now.