Results debunk theory linking statin use to Achilles tendon rupture, easing fears around exercise.

For years many clinicians and researchers theorized that statins—a cholesterol lowering medication that can reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke by between 25-35 per cent—were toxic to tendons and could increase the risk of tendon rupture. But new findings from a pioneering study led by Dr. Alex Scott, a Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute investigator, prove otherwise.

“Our study reassures patients with high cholesterol that taking statins should not have a negative impact on their Achilles tendons.”

High cholesterol is a buildup of fatty deposits in the body’s blood vessels that can restrict blood flow through arteries and can lead to heart disease, heart attack and stroke. Exercise assists with losing excess weight and maintaining a healthy body weight by reducing the amount of unhealthy fats in a person’s bloodstream. This makes it particularly important for patients with high cholesterol to lead active lifestyles to control weight and improve cardiovascular health.

“Patients may have been reluctant to take statins in the past due to the possible side effect of Achilles tendon rupture,” says Scott. “Yet, this potentially life-saving medication can be highly recommended for patients with elevated cholesterol levels because of its effectiveness at decreasing the risk of heart disease.”

Questioning previous findings could help high cholesterol patients

Scott became interested in researching statins after studying the effect high cholesterol has on musculoskeletal tissues—the tissues that support movement—particularly tendons. He and his team of researchers noted that patients who have elevated cholesterol levels tend to have tendons that are less stiff and less able to support the load of their bodyweight. This affects patients’ ability to move efficiently, even with such things as walking.

"Our previous research demonstrated that the tendons of people with high cholesterol tended to stretch more, which forced their muscles to work harder as a result.”

While conducting this research, Scott came across a study out of France that linked statins to Achilles tendon rupture—based on information sourced from a database of reported patient side effects. A United Kingdom study later refuted these findings using information from a large medical registry. The UK team found that bodyweight, age and various other factors could be contributing to an increased incidence of Achilles tendon rupture, and not the use of statins.

Scott and colleagues’ most recent study is the first to directly measure the Achilles tendon structure of individuals of a similar age and gender—33 of whom had been taking statins for at least one year and 33 of whom had never taken statins.

“We found no significant difference in the health of Achilles tendon tissues among individuals taking statins and those who had never taken statins.”

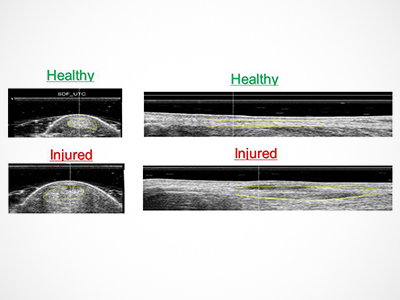

Statins were thought to cause structural changes to the collagen of the Achilles tendon. For their study, Scott and colleagues used the high-frequency sound waves of ultrasound technology to take pictures of Achilles tendon collagen inside the body. These images showed no difference in the structure and health of the collagen in either group of study participants. They did, however, find a connection between a higher body mass index (BMI)—the measurement of someone’s body fat based on their weight and height—and an increased risk of Achilles tendon rupture.

“We found that the higher someone’s BMI, the worse their tendon structure.”

Scott believes that this secondary finding could impact the rehabilitative exercises prescribed to patients with a higher BMI, who would likely need a slower progression of exercise intensity to protect against Achilles tendon inflammation and rupture.