Tetrahydroprotoberberines show potential for reducing both drug dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

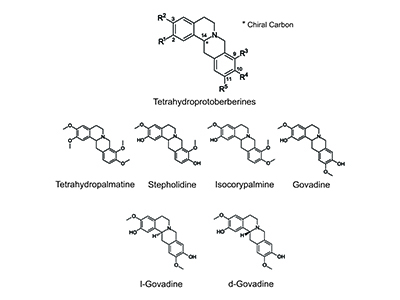

For more than two decades, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute scientist Dr. Anthony Phillips’s research on the brain’s dopamine system has dovetailed with his extensive work investigating plant-derived chemical compounds called tetrahydroprotoberberines (THPBs). In a review paper published in Trends in Pharmacological Science, Phillips and University of British Columbia (UBC) neuroscience PhD student Maya Nesbit looked at recent research discoveries from animal models of substance use disorder (SUD) that show significant potential for the use of THPBs to treat SUD.

In the 1990’s, research from the Institute Materia Medica in Shanghai suggested that a THPB molecule called l-stepholidine (l-SPD) could have opposite effects on two critical receptors in brain dopamine neurochemical systems. Remarkably, l-SPD appeared to excite one set of dopamine receptors while simultaneously suppressing the other.

“These two classes of dopamine receptors are strongly implicated in addiction and mental health disorders such as schizophrenia,” explains Phillips, who is a professor in the Department of Psychiatry in the Faculty of Medicine at UBC. “Decades of prior work suggested that a drug that could produce such opposite effects would be perfect for schizophrenia and potentially substance use disorder.”

According to Phillips and Nesbit’s review, studies based on SUD animal models suggested that a THPB called l-Tetrahydropalmatine (l-THP) dampened an animal’s drive to seek out and self-administer drugs such as cocaine, methamphetamine and heroin. At the same time, l-THP also showed potential for effectively treating substance-withdrawal symptoms.

Phillips’ interest in THPBs led him to work with Glen Sammis, an associate professor in the Department of Chemistry at UBC, who was able to synthesize novel analogs of the THPB l-SPD called d-govadine (d-GOV) and l-govadine (l-GOV). Phillips, Sammis and other colleagues were recently awarded a US patent for the use of d-GOV to selectively increase dopamine function in the frontal cortex as a means of improving cognitive deficits in schizophrenia and dementias.

Preliminary research also showed that 1-THP, d-GOV and l-GOV all appeared to reverse animals’ drug-cue associations, which made it easier for them to curtail their substance misuse.

“We know from animal models of addiction that an animal can develop a preference for an environment in which it had previously received amphetamines, or has a memory of the potentially addictive properties of the drug; and if you keep exposing it to that same environment but without giving it any drug, it eventually loses this preference,” explains Phillips. “The evidence suggests that d-GOV in particular greatly accelerates how quickly an animal will lose the memory for the place where it had received the drug previously. That’s how Maya and I became interested in thinking about THPBs as promising chemicals that might have some relevance to controlling addiction.”

“We’re currently looking more at aspects of opioid misuse and THPBs. But the common theme running through all of this is an action of these drugs on the brain dopamine systems. Everything we do points to those systems being a specific target of these THPBs.”

“At a time when novel therapeutics for substance use disorders are desperately needed, optimization of THPB drug design have revitalized efforts to improve the clinical viability of THPBs,” explain Phillips and Nesbit. “Future research should test the effects of existing and novel THPBs on the escalation of drug taking, incubation of drug craving, and other high-validity models of SUD. Finally, the ability of THPBs to facilitate cognitive control over motivation for drug seeking warrants further study.”