Researchers hear directly from people with lived experience to help families navigate Western approaches to advanced care.

End-of-life care is never an easy topic of conversation. For people of South Asian descent, discussions about death and dying can also carry with them cultural norms and family traditions that differ from those of mainstream Western cultures, which the health care system in British Columbia is largely built upon.

Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) researcher Dr. Amrish Joshi has thought deeply on the topic, both as someone of South Asian descent and as a community palliative physician with the Richmond Integrated Hospice Palliative Care Program.

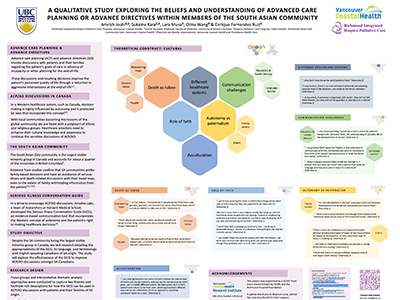

His research study is designed to raise awareness about advanced care planning among English-speaking Canadians of South Asian origin.

Working alongside another physician of South Asian heritage, as well as two nurses of Filipino and Chinese descent, Joshi conducted five focus groups on the subject of end-of-life care with 18 South Asian participants from the general public.

Participants had the opportunity to talk with Joshi and his research team in an informal setting about their values, beliefs and life experiences when it comes to serious or terminal illness, taking the perspective of both patients and family members.

“Our research has shown that culture matters when it comes to how and when individuals are prepared to talk about death and dying,” says Joshi.

“Acculturation, or how long a person has lived in Canada and how much they have picked up Western ethics and practices, can also influence how comfortable someone is when it comes to talking about end-of-life care.”

Joshi found that participants who had only been in the country for a couple of months were more reluctant to speak on the subject, versus individuals who have lived in Canada for many years.

Western medicine values autonomous decision-making that puts advanced care planning into the hands of the individual. In the South Asian community, physicians are typically seen as authority figures whose word should be taken at face value. Decisions about advanced care planning are viewed as a collective responsibility.

Children of a dying parent are often tasked with providing the main sources of care and support. Sometimes, cultural norms may guide them to not disclose the severity of an illness to their loved one in the interest of preserving hope, notes Joshi.

Religious views, levels of education and language barriers were also identified in Joshi’s research as factors that influenced how participants navigated through the advanced care planning process.

Culturally appropriate language can bridge barriers and optimize care

In Greater Vancouver, the South Asian community represents one quarter of all visible minorities. While many prefer to make family-based decisions, they often refrain from engaging in discussions about serious illness and death, both of which are essential to planning for end-of-life care, says Joshi. This can prevent some families from taking full advantage of available advanced care services.

For his research study, Joshi and his team introduced study participants to the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, a research-based communication tool that explores Western notions of autonomous decision-making surrounding advanced care planning. While not a replacement for culturally sensitive care, researchers believe that exposure to the guide could help people of South Asian origin navigate the Western advanced care system.

“Western cultures tend to be more individualistic, which is represented in the guide’s concept of autonomous decision-making.”

“For the South Asian community, having family present during advanced care planning conversations is important, as patients often reframe questions about their advanced care goals to family goals,” notes Joshi.

The feedback and lived experiences Joshi and his team collected from study participants can also contribute to discussions about how to provide culturally appropriate care, and potentially develop new supplementary tools to the Serious Illness Conversation Guide, adds Joshi.

“With more cultural awareness, we can increase the skill set of health care practitioners and improve patient care,” says Joshi. “Conducting this research has already helped me build trust with my patients in my current practice.”