Researchers discovered that kidney patients who were the hardest to match with donors were not receiving the priority they required.

There are currently over 550 patients in British Columbia on a waitlist for a kidney transplant. New research led by Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher Dr. James Lan — published in the American Journal of Transplantation — found that the system used to prioritize patients who are difficult to match with a potential donor has overlooked an important variable: their blood type.

“The game-changer we discovered was that, if you were in blood group O or B, you were likely to be more disadvantaged when it comes to being prioritized with a kidney,” says Lan.

“Giving a kidney to the right patient at the right time is predicted to increase the efficiency and fairness of the kidney transplant system as a whole.”

Kidney candidates on the transplant waitlist are currently screened for the presence of antibodies against immune molecules called human leukocyte antigens (HLA).

HLA sensitization occurs when a person’s immune system is exposed to HLA molecules that are foreign to their own body. For example, in the event of a blood transfusion or pregnancy, an individual’s immune system recognizes the HLA proteins of the blood product or fetus as foreign, thereby triggering an immune response to produce anti-HLA antibodies.

For decades, it has been known that antibodies directed against a donor kidney can lead to severe kidney rejection. Because of this, HLA sensitization can make it challenging for a kidney patient to find a matching donor.

“For some patients, their calculated panel reactive antibody (cPRA) — a measure of how likely their body will react to a random kidney donor — is zero, which means that they can match with any kidney donor,” explains Lan. “Other patients may have a cPRA of 99 per cent, meaning that they only match with one donor out of 100.”

Patients with a cPRA of 95 per cent or higher are placed in the hard-to-match category and receive priority status, adds Lan. Priority status gives patients access to donors from across Canada instead of only within their province of residence, as is the case for non-priority-status patients.

“It is essential to give priority status to a patient for whom it will be hard to find a matching donor.”

What Lan and his team discovered was that HLA sensitization is only part of the picture when it comes to determining a patient’s cPRA. The missing element is the consideration of patients’ ABO blood type.

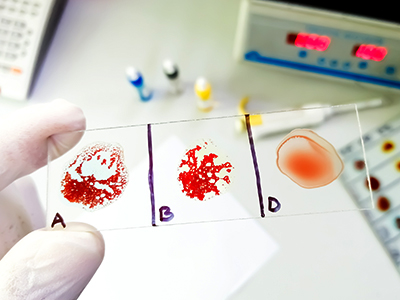

For instance, blood type O patients can only receive kidneys from donors that are also blood type O. Blood type A patients can only match donors that are blood type A or O. Similarly, blood type B candidates can only match with blood type B or O donors. In contrast, blood type AB patients can receive a kidney from donors with any blood type.

This means that patients with O blood type have a more limited donor pool than other blood types, yet blood type was previously not considered when determining whether a patient should receive priority status or in the ranking of priority.

The new blood type inclusive model, called the ABO-adjusted cPRA, designed by Lan and his colleagues addresses this missing piece of the puzzle. By integrating blood type into the equation, the ABO-adjusted cPRA more accurately captures all hard-to-match kidney patients, ensuring that they get appropriate priority when a match becomes available.

The ABO-adjusted cPRA system was developed in collaboration with Dr. Loren Gragert from the Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans, Louisiana. Gragert brought to the team essential technological know-how in the areas of HLA informatics and population genetics datasets used in kidney donor registries.

Gragert and Lan’s novel calculation, which merges ABO and HLA sensitization to compute overall immune sensitization in a single metric, is a global first to their knowledge, says Gragert.

Giving kidneys to patients who need it most

Dialysis patients receive treatment using a dialysis machine that removes waste, extra water and salt from their bloodstream that their kidneys are no longer able to adequately process. Dialysis also rebalances chemicals in the body, as well as blood pressure.

While dialysis is an essential, life-extending procedure, patients on dialysis awaiting a kidney transplant have around a 50 per cent chance of survival after five years, making it a race against time to find a matching donor.

“Patients on dialysis often cannot work, they feel terrible the day they receive dialysis and the day after because the procedure completely drains their energy,” explains Lan.

“Getting patients off of dialysis as soon as possible can dramatically improve their longevity and quality of life.”

In addition, dialysis costs the health care system around $100,000 per year per patient, Lan adds, versus $20,000 per year for anti-transplant medication.

“The system works better when hard-to-match patients receive appropriate priority status,” says Lan. “This might be their only opportunity for a match, versus patients with a bigger pool of eligible donors who are more likely to find a match within the first five years of being on dialysis.”

“The ABO-adjusted cPRA metric is a more accurate approach that places a kidney in the patient who needs it the most so that they will not miss out on a potentially once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.”