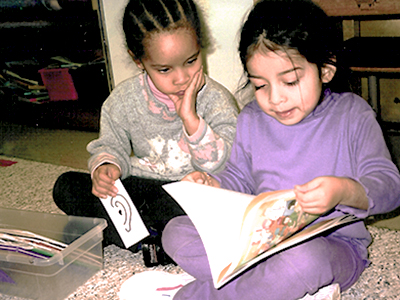

The Tools of the Mind curriculum places equal emphasis on children’s academic and social-emotional skills.

On an average day in many kindergarten classrooms, you might see toys thrown through the air, one child push another and tears. This kind of misbehaviour not only impedes learning, it can cause a lot of stress among teachers and students.

In her study, Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher Dr. Adele Diamond investigated the impact of Tools of the Mind—a curriculum for young children—on such things as academic outcomes, self-control and teacher satisfaction.

“We found that, when children are taught how to exercise self-control and self-regulate their emotions, all kinds of doors to learning open up.”

Tools of the Mind was created by educational psychologists Elena Bodrova and Deborah Leong in the 1990s, and based on the work of psychologist Lev Vygotsky. The Tools approach to learning teaches children how to manage their emotions and interactions with others. With these skills in hand, Tools posits that children will be better able to work collaboratively, concentrate and excel academically.

Better academic performance and peer-to-peer behaviour

Diamond’s study, the first randomized control trial of Tools of the Mind among Canadian kindergartens, examined 18 classrooms in Greater Vancouver—nine schools that implemented Tools and nine control schools with a standard, non-Tools curriculum.

All students in the eight-month study, which began in September, had relatively similar reading, writing and math skills to begin with.

By May, the study results showed that 89 per cent of Tools classrooms had more than two students reading at a Grade 1 level or higher, compared with only 11 per cent of the control classrooms. Similarly, by then 30 per cent of Tools students could write a full sentence with most sounds in the sentences properly represented, compared with 10 per cent of control students. There was no significant difference in math scores between both groups.

At the start of the school year, 89 per cent of all teachers reported that their students had difficulty getting back to work after spring break. By May, Tools teachers said the opposite was now the case in their classrooms, compared with only 56 per cent of control teachers.

Tools students were able to concentrate longer by May—12.3 minutes compared with 5.1 minutes among control students. They also helped each other more than the control students did.

“They offer help and assistance when needed without being asked and without belittling the struggling student,” commented a Tools teacher.

“They look out for one another and ensure everyone has someone to play with or talk to.”

Teacher satisfaction was also higher. Over 75 per cent of Tools teachers reported feeling excited about teaching, while this was not true for any control group teachers. Similarly, all Tools teachers said they were looking forward to teaching kindergarten the next year, while only two control teachers felt the same way.

“If a teacher is stressed, this can have an effect on the students in the class,” notes Diamond. “We need to pay more attention to teacher well-being, as well as student well-being to ensure better learning outcomes.”

When students are better able to manage their emotions and work together, teachers are in a better position to conduct the day’s lessons and derive greater satisfaction from their work, adds Diamond.

“We know that what happens early in life lays a foundation upon which everything else builds. So, if we can build on a healthy foundation where kids feel valued and not stressed, then everything else will be on more solid ground moving forward.”