The first-of-its-kind study uses advanced MRI technology to visualize the mechanics of this key vehicle safety feature.

The seat belt is one of the most important safety features in a motor vehicle, saving around 1,000 Canadian lives each year. Yet, since its development in the 1950s, little empirical evidence has been gathered about how wearing a seat belt protects females and males of different ages.

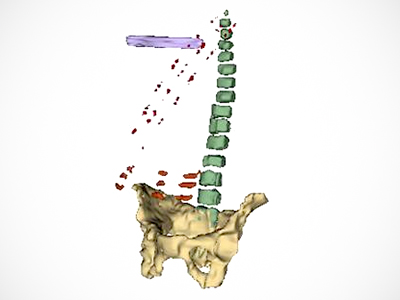

Dr. Peter Cripton, a Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher, is conducting pioneering research to collect data that could revolutionize the seat belt. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology, he and his team will visualize how seat belts rest against the musculoskeletal structures — the bones and soft tissues — of females and males between the ages of 19 and 60.

Prior studies, including one from 2019, have found that seat-belted females were 73 per cent more likely to sustain a serious or fatal injury in the event of a head-on collision than their male counterparts. By examining females and males of different ages, Cripton’s research will gather first-of-its-kind foundational data on belt mechanics and body positioning.

“We have known for a long time that women are more likely to sustain a serious injury in the event of a crash, and that this may be linked to seat belt dynamics on different female body types that have yet to be explored,” says Cripton.

Unique MRI technology provides new insight into seat belt impacts on the body

Cripton’s research uses the world’s only Upright Open MRI dedicated to research, which is housed in the Centre for Hip Health and Mobility. Unlike traditional MRIs, Open MRIs consist of two high-powered and non-ionizing, that is, benign, radiation walls with a space between them in which a person can take a variety of standing, sitting or prostrate postures.

Participants in Cripton’s study will be buckled into a seat placed between the Open MRI machine’s walls to see where the belt rests in relation to their bones and tissues, including internal organs.

The study seat and three-point seat belt are modeled after those found in contemporary passenger vehicles with the exception that all metal material is substituted with plastic clamps, as any metal would be torn out by the MRI’s powerful magnets. Three-point seat belts are designed to cross the shoulder and hips of a passenger.

This image was shared with the participant’s permission.

Special oil-filled markers are glued to the seat belt to help the research team visualize its routing. This is particularly important as it enables Cripton and his team to visualize where the seat belt rests in relation to participants’ hip and clavicle or shoulder bones.

“The clavicle is one of the strongest places to support the body during a crash,” explains Cripton. “The belt needs to be able to rest securely against it to prevent a passenger from slipping to one side of the belt or forwards. Any slippage out of the belt can put a passenger at risk of hitting hard parts of the vehicle, such as a car door, dashboard or steering wheel.”

Fitting seat belts for different body types, reclined positions and autonomous vehicles

Back when the automobile industry was first developing seat belts, regulators okayed the calibration of the safety devices based on the average male’s height and build — policies that remain in place today. As Cripton notes, “this does not really translate into a representation of 50 per cent of the human species.”

A person’s height, as well as the presence of breast tissue or a pregnant belly, can move a seat belt away from its optimal position. Women’s bodies also tend to be wider in the hips and have more tissue concentrated around the waist and thighs, while men tend to have more extra tissue on the belly, according to some experts, which may also play a role in overall seat belt effectiveness.

“The data we collect may shed some light on how differences in sex and age affect belt positioning in the event of a crash.”

Cripton’s study will also collect data on seat belt positioning on participants in a reclined position. This takes into consideration belt design for people in this unsafe position, and a potential driverless car revolution in which people may be allowed to recline or take other seated postures.

Once his study is complete, Cripton aims to move his research into practice. Working with partners and stakeholders, he anticipates lobbying governments to improve seat belt standards and best practices.

Cripton is currently collaborating with researchers at the University of Virginia, as well as working with representatives from the Swedish-headquartered automotive safety supplier Autolivi, the British and US electric vehicle manufacturer Arrival Ltd., and the Vancouver-based forensic engineering company MEA Forensic.

“At the end of the day, the work we are doing is all about preventing injury,” he says.

Cripton’s study, Effects of sex on belt fit in relation to skeletal geometry, is currently recruiting participants ages 19-60. For more information, contact gabrielle.booth@ubc.ca.