Researchers discover a significant post-race decrease in cognitive function among ultra-endurance trail runners.

Ultra-marathon running has been linked to the temporary lowering of cognition and memory, according to the findings of a study led by Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher, Dr. Darren Warburton.

“While the benefits of physical exercise far outweigh the risks, it is important to note the potential hazards associated with marathon running during and for a period of time following a race,” says Warburton. “Our research study enters into the territory of discovering what might be the upper limits of the benefits of exercise.”

Published in Frontiers in Physiology, Warburton’s study identified significant cognitive declines in ultra-marathoners directly following an ultra-endurance trail race.

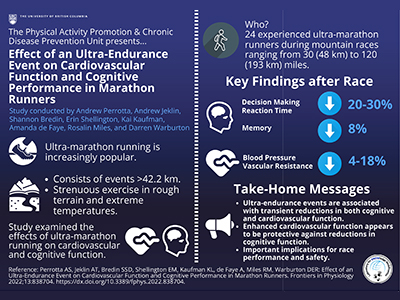

The study examined 24 experienced ultra-marathon runners — 19 males and five females — who ran either around 48, 81, 113 or 193 kilometres consecutively in the FatDog120 ultra-endurance trail race in British Columbia.

Researchers took readings of participants’ heart rate, blood pressure and cognitive performance before and after the race. Cognition was measured in terms of participants’ simple processing speed, ability to discriminate between objects and choice-making abilities when shown a series of coloured dots. Participants’ memory was also tested through their ability to remember a selection of playing cards.

Warburton and his team found that racers’ post-race simple processing speed reaction time decreased by around 30 per cent, their ability to discriminate between different objects decreased by around 23 per cent and their choice reaction time was impaired by about 31 per cent. As well, participants’ memory recall dropped by approximately eight per cent.

“A 20 to 30 per cent drop in cognition is a significant finding, and much higher than we anticipated.”

“Athletes competing in these ultra-marathon events can sometimes be in sub-zero conditions at night and above 40 degrees Celsius during the day, running 20 to 30 hours,” notes Warburton. “Sometimes the terrain may involve narrow mountain passes with steep drop-offs that require athletes to be alert and aware of their surroundings.”

"Our findings point to a need to investigate medical strategies that race organizers can implement to further prevent athlete injury.”

Many safety measures are currently in place at ultra-marathons, including aid stations where athletes can rest, receive any required medical first-aid and replenish their electrolytes and fluids. However, enhanced athlete safety could involve additional monitoring of athletes’ cognition at aid stations and after the race, says Warburton. As well, organizers may add safeguards to ensure that athletes are given adequate access to places to rest and recover after a race and are informed about the importance of rest following an ultra-endurance event, Warburton adds.

Managing race risk among elite runners

Warburton began working with performance athletes with cardiac arrhythmias around 20 years ago. Arrhythmias are abnormal electrical signals in the heart that can lead to an irregular heartbeat and sometimes dangerous conditions, such as stroke and heart failure. Over the course of his career, Warburton has noticed a pattern in the development of both short-term cardiac events and long-term cardiac arrhythmias among performance runners.

The known link between cardiac and cognitive function prompted Warburton and his collaborator, Dr. Shannon Bredin, to investigate how cardiac effects observed in their prior research might impact the cognitive function of elite runners.

Warburton and colleagues’ present study revealed significant changes in post-race cardiovascular function. Athletes’ resting heart rate was up around 32 per cent, their cardiac output increased by about 28 per cent and their mean arterial blood pressure was down by approximately six per cent. These effects were recorded alongside the observed cognitive impairments, suggesting a link between the two.

“Our body functions compete for a finite supply of oxygen,” explains Warburton. “After many hours of exertion, the heart muscle can begin to fatigue, blood pressure lowers, mental fatigue sets in and muscles may draw blood away from other organs, such as the brain.”

The age of participants — an average of 37 years — may have also influenced the cognitive results, notes Warburton. Previous research has found that cognition, in terms of simple reaction time and choice, tends to decrease over a lifetime, particularly after the age of 50.

More research is needed to determine the exact mechanisms at play behind the observed significant reductions in cognitive function among ultra-marathon runners. However, Warburton hopes that this study is the first step along the path to a deeper understanding of the temporary impacts of long-distance running on cognition and the implementation of measures to reduce associated risks.