Research calls for better diagnostics and interventions for non-HPV vulvar cancer.

Recent media coverage has raised awareness about the importance of human papilloma virus (HPV) testing and vaccination, but less attention has been paid to non-HPV forms of vulvar cancer. Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (VCHRI) researchers have found that previous diagnostic approaches and less aggressive treatments resulted in worse, and often deadly, outcomes for women.

Two recent papers co-authored by Dr. Blake Gilks, Dr. Jessica McAlpine and colleagues—a retrospective cohort study and research paper—call for better screening and more aggressive treatment when suspicious lesions are detected.

“Our recent papers are a clarion call that we must treat these HPV and non-HPV diseases as distinct conditions because they behave differently and have different treatment needs,” says Gilks, who co-founded OVCARE—a gynaecological cancer research institute at Vancouver General Hospital (VGH).

“Vulvar cancer is not one disease, but we have been treating it as such.”

In British Columbia, around 40 cases of vulvar cancer are diagnosed each year. The most common form of vulvar cancer is vulvar squamous cell carcinomas (VSCCs)—cancers that affect the squamous cells, or outer layer of skin, of a woman’s vulva.

Clinicians now know that HPV status changes the risk of developing vulvar cancer and the deadliness of the disease. Around 50-60 per cent of cases are related to HPV infections and usually affect younger women, many of who have a prior history of benign warts.

The other 40-50 per cent of cases are non-HPV-associated VSCC and mostly affect women over age 50. Non-HPV VSCC often appears as lesions or abnormal tissue similar to benign inflammatory conditions or general vulvar irritation, making a cancer diagnosis easier to miss.

“Our research shows, for the first time, the urgency of treating patients with non-HPV vulvar cancer precursor lesions early to prevent the disease from becoming deadly.”

“More aggressive surgery needs to be done to excise non-HPV vulvar cancer tissue,” says Dr. Lien Hoang, a VCHRI researcher and surgical pathologist at VGH. "Non-HPV VSCC also tends to be more resistant to radiation therapy in comparison to its HPV-related counterparts.”

Of similar concern is the fact that getting the HPV vaccine will not protect women against non-HVP VSCC. With an aging population, the number of cases of non-HPV VSCC could climb in coming years, notes McAlpine.

Better and more tailored care for women with vulvar cancer

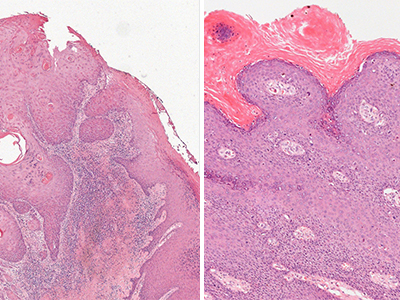

The process for diagnosing HPV-related tumours has been perfected over the years, says Hoang. A biopsy is taken and sent to the pathology lab. Even junior clinicians have little difficulty distinguishing between benign and cancerous forms of the disease.

Conversely, early-stage non-HPV VSCC “is very hard to diagnose,” notes Hoang. “Even world-renowned pathologists would have a really difficult time making a diagnosis because the features of the disease are not as easily recognizable. This is why we are pushing to develop better ancillary tests for early detection.”

“We need to catch this disease early to prevent the rapid progression of a patient’s condition.”

Prior to the year 2000, cases of non-HPV VSCC were often categorized as outliers. The surgical procedure to excise a non-HPV VSCC tumour was more conservative than it is today. Clinicians removed less tissue, which sped up healing and recovery time but resulted in a three-fold increase in disease recurrence and mortality rates.

“Advances in vulvar cancer treatment have lagged behind other cancers,” says Hoang. “Now we are really focusing on a personalized medicine approach that involves specific treatments for specific vulvar cancer types.”

“We have chemical and molecular tests that we can do that go beyond looking at tissue samples under a microscope,” she adds. “There is a heightened vigilance and closer follow-up to prevent a missed recurrence of the disease.”

The research of Gilks, Hoang and McAlpine is charting a course for improved diagnostics and treatments, says Gilks. Their papers include illustrations of what to look for and descriptions of challenging cases of non-HPV VSCC.

This research could help shape clinical and diagnostic practices, as well as the transfer of knowledge at educational institutions and through medical textbooks.

“However, there remains a lot to be learned,” says Hoang. “We are still in the discovery phase of this condition, and are working on coming up with uniform terminology and criteria in order to help clinicians and pathologists make more precise diagnoses.”