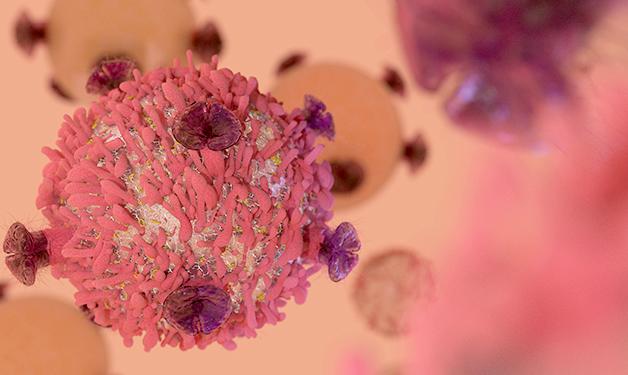

Cancer marker cell identified as a potential immune system-boosting, cancer-fighting agent.

Scientists with Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute have discovered an immune cell and immune growth factor in tumours that appear to play a pivotal role in preventing the spread and growth of cancer. Dr. Wilfred Jefferies and co-authors published their findings in Scientific Reports (Nature) in February 2018. They found that Type-2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2)—only discovered within the past 10 years—could help the body’s immune system find and destroy cancer cells.

“I am incredibly excited about the results of this research. As someone who has lost many family members to cancer, I know the importance of finding better treatment solutions.”

“Understanding the mechanisms that promote an initial tumour to spread is of great concern, as the spreading of metastatic cancers accounts for 90 per cent of all cancer deaths.”

Jefferies and co-authors found that ILC2 strengthens the immune response that attacks cancer cells. When a cell mutates, as in the case of cancer cells, the body’s immune system is triggered to jump into action and destroy it using immune cells, such as T-cells. If left unchecked, mutated cells can multiply and turn into a cancerous tumour.

The recent work of Dr. Jefferies and his team uncovered a new form of cancer immunoevasion—when cancer cells avoid being destroyed by the body’s immune system. ILC2s are activated by a protein called interleukin-33 (IL-33), which Jefferies previously discovered also helps the immune system identify cancer cells. A problem arises when mutated tumour cells turn off IL-33 and ILC2s become inactive.

“A lack of IL-33 and ILC2 makes it easier for cancer cells to fly under the radar of the immune system, giving tumours an opportunity to grow and spread,” says Jefferies. “When ILC2s cells and IL-33 are present, the immune system is able to identify cancerous cells and destroy them.”

Discovery aims to make cancer cells visible to the immune system

Immunotherapy approaches to cancer treatment help the body’s natural immune system identify cancer cells so that it can attack them. It is one of several approaches—including surgery and chemotherapy—to treat cancer, and one that has seen substantial development since Paul Ehrlich suggested in 1909 that the immune system could suppress the formation of tumours.

In their paper, Jefferies and co-authors note that cancerous tissues lacking in ILC2s showed a significant increase in tumour growth rates and a higher propensity for cancer cells to spread, or metastasize, to other parts of the body. Conversely, they discovered that ILC2s can enter tumours and trigger the immune response. IL-33 is needed for the development of ILC2, and was also present in tissues that seemed to be protected against cancer proliferation.

“Currently only a minority of cancer patients respond to existing immunotherapies. Discovering new and better treatment options is a priority.”

The next step, Jefferies says, is to test their findings in clinical trials, likely starting with prostate and bladder cancers at the Vancouver Prostate Centre. The ultimate goal, he says, is to develop new and more effective immunotherapeutic treatments for cancer.