Researchers uncover novel variation in endometriosis genetic mutations and types that could be used to develop a new classification system.

Often called an invisible disease, endometriosis can have a significant negative impact on a person's physical and mental health. A recent study suggests the condition affects around seven per cent of Canadians of reproductive age who have a uterus, though the actual number may be higher. Many individuals seeking diagnosis and treatment experience a diagnostic delay of more than five years. There is no known cure, making research into the underlying mechanisms of the condition imperative to improve patient diagnosis, treatment and outcomes.

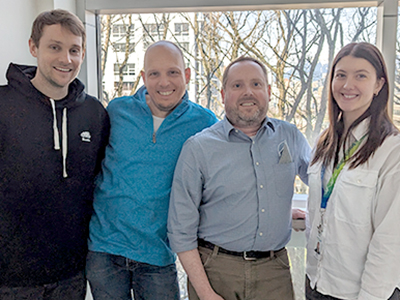

Prior research has aided in the classification of several distinct types of endometriosis. New research led by Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute researcher Dr. Michael Anglesio and published in the journal Fertility and Sterility has expanded the understanding of the disease to include a much broader array of mutations.

“Our study identified a relatively large number of mutations and many lesions with different types of mutations,” Anglesio states. “This adds a layer of complexity to our understanding of endometriosis.”

A stepping stone to potential precision diagnostics and treatments

For his study, Anglesio and his research team examined 73 endometriosis lesions from 27 patients between the ages of 23 and 45 years. Using high-tech equipment that enabled them to zero in on cells’ genetic components, they discovered a larger variation in mutations within endometrial cells than had been previously identified.

“Even though the cells we examined looked like normal endometrial cells under a microscope, at the genomic level, they were not as normal as they appeared to be,” explains Anglesio.

“We think only around one per cent of endometriosis will develop into cancer, but about half of the endometriosis we observed have cancer-like mutations that are a legitimate concern.”

Like all cells, normal endometrial cells have two copies of the genome — one inherited from each parent. However, cells in the endometriosis lesions Anglesio and his team dissected sometimes had four or five different activating mutations in the same gene.

“We observed that different mutations had occurred in different cells, and that this variation differed between patients,” says Anglesio.

"This study helps us better understand the heterogeneity of these mutations between patients, which could reveal clues as to why some individuals are asymptomatic while others may have severe pelvic pain.”

Anglesio believes that some of the genetic variation he and his team observed is likely due to influences from the location in the body where the endometriosis cells migrated, such as the ovaries.

The research team also noted some patterns between different types of endometriosis. For example, patients with ovarian endometriosis had more mutations within each lesion, but there was less variation in genes affected in these endometriomas between patients. Conversely, the research team observed fewer mutations per patient and a wider range of mutations between patients with deep-infiltrating endometriosis, which is an invasive form of endometriosis typically found in the lower pelvis.

Anglesio’s findings bring research closer to a potential new classification system for endometriosis that could lead to precision medicine diagnostics and treatments.

“This research is a stepping stone that we needed to paint a better picture of the complexity of the condition,” Anglesio notes. “Further research could bring us to the point of identifying treatments that target specific endometrial mutations.”